Values aren’t universal, but power is

Culture and power in determination of the new world order

West-South divergence

A little noticed dichotomy has emerged in global attitudes towards Donald Trump and the United States that likely materially affects his chances of success in remaking the global political economy. While it will come as no surprise that President Trump is unloved and tarnishing the American brand in the West, you might be surprised to learn that the so called “Global South” has a more favorable view of him that has benefitted perceptions of America (Figure 1). Indeed, his highest approval comes from one of the nations he referred to as a “sh*thole” in his first term.1 This puzzling divergence likely derives from a source that markets rarely heed – culture – but given the stakes, they should.

¡Mi culture es su culture!

The source lies in a deep Western misunderstanding about culture that pervades the post-War liberal order (PWLO). The US-built “rules-based” order sits on a foundation of “universal” values that bear a suspicious resemblance to those of Anglo-Saxon Protestantism.2 Yet, as Global entropy has eroded US hegemony, an increasing number of non-Western nations – originally as the “anti-colonial” and “non-aligned” movements, and more recently under the banners of “BRICS” or “multipolarity” – are chafing at these universal values.3 The West’s reaction to those warning signs has been to evermore stridently assert the universality of its values through conditional lending and aid, or even through force of arms. Predictably, resentment has grown in the rest of the world.

Cultural distance

In Global entropy: Enter the dragons (free at Thematic Markets), I describe how the West’s strategic rivals in China, Russia and Iran have exploited both cultural differences and the West’s stubborn denial of them to hasten the PWLO’s demise. I refer readers to that (very long) article for details, but Figure 2 reproduces one of its main analyses. Based on responses of 94,000 interviewees to the 259 questions in the World Values Survey, I calculated the mathematical distance of the 107 surveyed countries’ values from the average Western nation along two axes: Personal values related to family, the role of women, sexuality, and religion; and quasi-ESG (environment and social governance) values of individual freedom, tolerance and environmentalism. Contrary to a central tenant of the PWLO, most countries of the world have very different values to the West. Interestingly, even the leading Western nation, America, is quite culturally different to the average of its Western allies.

“Too oyinbo”

A personal anecdote may help cut through the abstraction to illustrate how cultural differences relate to Donald Trump’s foreign and economic policy. Although we met and live in London, my fiancée and I are from very different cultures. I was born and raised in the Western US, while Joy was born and raised in Lagos, Nigeria (although she was sent to boarding school in England at an early age). A few years ago, we were preparing to let our house with economical furnishings. We found about a dozen suitable items at a used furniture shop. When it came time for us to buy, Joy insisted on handling the negotiations because I am, in her words, “too oyinbo” (white).

What followed was as dizzying for me as for the poor, unprepared English salesperson. Joy traversed the shop, up and down the stairs, from room to room in no particular order, pointing to both random pieces and ones we had selected, requesting discounts of differing percentages on each, frequently “changing her mind” to swap or give up pieces, and, whenever the sales person resisted, asking for free deal-sweeteners or re-dealing on already-agreed prices. After 20 minutes, the exasperated salesperson literally tried to walk away, but Joy, ever polite, kept pressing. In the end, we walked out with everything we wanted at a price so low that the shop owner refused the free delivery Joy negotiated because she already was losing too much money on the furniture!

Confusion is the point

The confusion – random order, asking for things she didn’t want, constantly changing her mind, asking for discounts of seemingly random percentages, changing tack to ask for free things or redeal – was intentional, designed to keep the salesperson off balance and unable to see a pattern that he might exploit while Joy used his confusion to her own advantage. While Donald Trump lacks Joy’s English boarding-school manners, he uses the same confusion strategy in both domestic and foreign policy negotiations. The incessant salvos of seemingly random, ever-changing demands, bizarre pronouncements, alternating insults and flattery, delivered in all caps on Truth Social or as an “off-the-cuff” remark on Air Force One, badgering heads of state in the Oval Office, or backslapping a Fed Chairman he called a “numbskull” the day before is theater designed to keep the President’s opponents bewildered and disadvantaged.

Cultural dissonance

Joy is right, I am too oyinbo. Raised in California’s hypermodernity, I not only cannot bargain the way she does but find it disconcerting (of course I paid the delivery fee). Westerners expect printed, non-negotiable prices, seasonal sales with standard markdowns, well mannered queues at the till, and equal treatment as long as you have the money to pay. When someone attempts to break those rules, we experience the discomfort of cultural dissonance.4 But most of the rest of the world doesn’t work that way. Like values, neither queuing, nor posted prices are universal; most things are negotiated hard; and discounts are given for status, tribal and religious affiliation, or expectations of a return favor.

A man they can deal with

Where Westerners see in Donald Trump’s style and substance a crass, violation of norms and erosion of the “rules-based order” or even democracy itself, many other cultures recognize his demands for what they are: haggling at the market for the lowest price. It appears that they see in Donald Trump a man that they can deal with. Like the Chinese or Russians, he doesn’t demand that they accept his universal values, change their election laws, or conform to ESG. He doesn’t object to bribery and is happy to support crypto payments (stablecoins) that lack know-your-client vetting.5 But he does negotiate hard, pressing every advantage the US has – and the US has leverage over most countries – while acknowledging cultural and political redlines and, like all experienced negotiators, leaving small, face-saving “wins” on the table, like Iran’s unanswered performative missile salvo at a US base in Qatar. (For the record – and the harmony of my relationship – I must note that while Joy understands President Trump, she does not like him.)

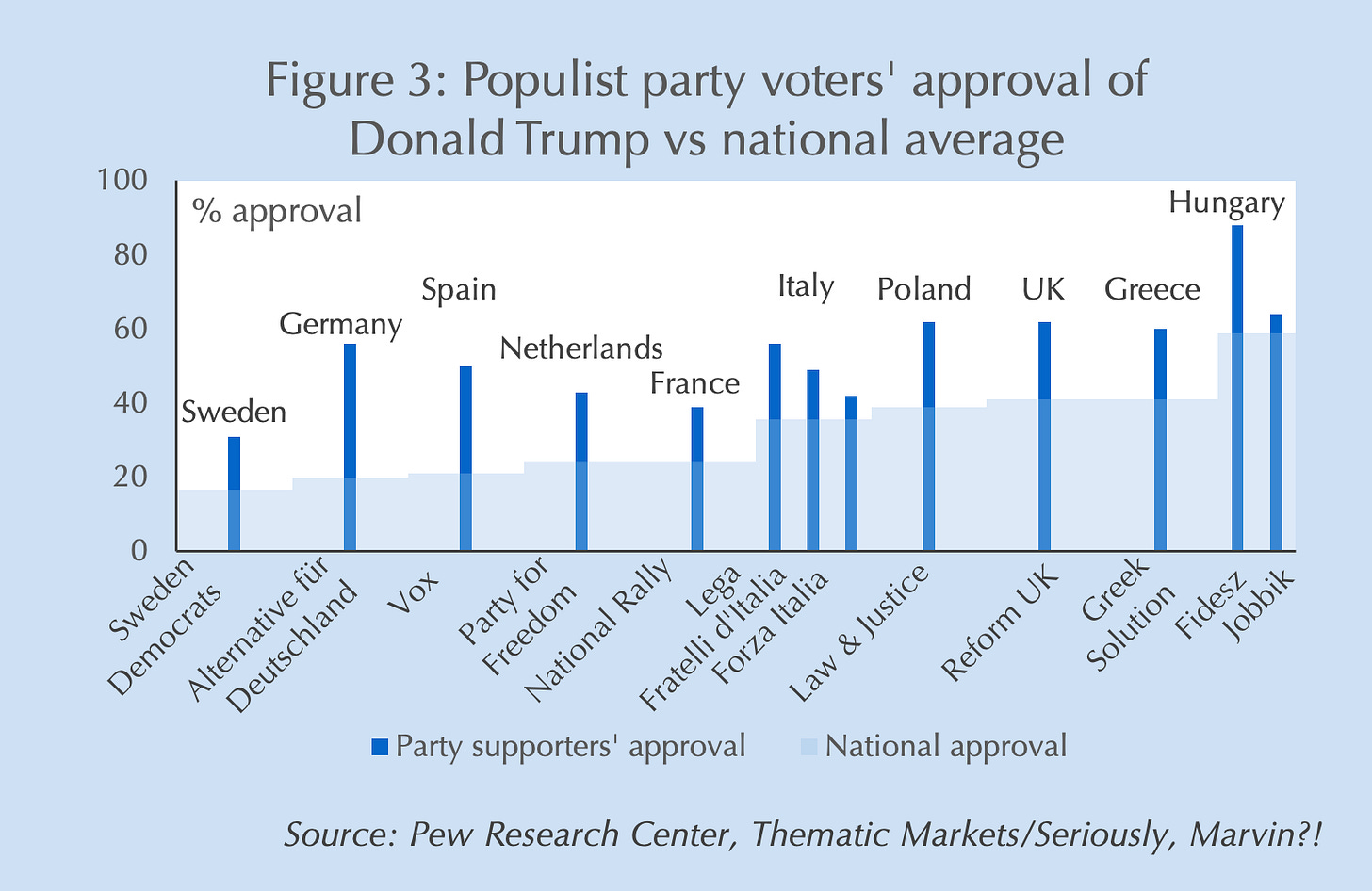

[My country] firsters unite!

Even within the West, President Trump finds pockets of support. Mr. Trump scores highly among populists, even when a country’s broader population dislikes him (Figure 3). That’s because “America first” complements rather than contradicts “[My country] first.” In the eyes of my-country-firsters, President Trump’s foreign policy demotes the same international institutions and supra-sovereign entities they view as eroding their own sovereignty and refocuses inter-state negotiations on hardnosed national interests.

Conversely, many elites – especially bureaucrats – in countries with high approval of President Trump, intensely dislike both him and his policies. This may reflect their incentives: across economies, the greatest beneficiaries of both globalization and the “rules-based order” have been the elites that write those rules, manage international institutions, and are best positioned to manipulate both to their own advantage. President Trump’s populism and policies threaten their livelihoods and sources of power. That might well explain why approval rates for Mr. Trump in Figure 1 appear to be correlated with country income inequality: the fewer and more powerful the elites, the greater the share of the population approving of his policies.

Respect and saving face

Yet, the rest of the world is not culturally amorphous and not all non-Western countries appreciate President Trump’s approach. Respect and face saving are important to many cultures in East Asia, and some, like Japan and South Korea, eschew bargaining. For them, Mr. Trump’s approach is as offensive as it is to most Westerners. Furthermore, it remains to be seen how durable Mr. Trump’s popularity will remain in countries like India where he has imposed punitive tariffs for buying Russian oil, or in counties like Indonesia and Vietnam that were coerced into lopsided trade deals with a far richer country.

Power politics

The co-mingling of economic and foreign policies adds another dimension. President Trump’s second-term policies are accelerating a trend that began in his first term and was carried on by the Biden Administration, i.e. increasing emphasis on national security in economic policy. The high additive tariffs imposed on Brazil and India show that Mr. Trump wields tariffs the way previous US presidents did gunboats, or more recently, sanctions.6 Collectively Mr. Trump’s approach reflects what I’ve called La Cosa Nostra Americana foreign policy. To be a member of the family in good standing, you must pay not only tribute but fealty to the Don. Failures of fealty are punished with higher tariffs, loss of access to your network servers and email, or perhaps worse.7

Better feared than loved?

But as critics point out, President Trump’s coercive foreign and economic policies run the risk of permanently damaging world opinion on the US. Yet stable international relations are rarely based on popularity. Stability comes either from an alignment of interests or from fear: fear of reprisal or, more frequently, fear of the alternative. Donald Trump’s America is not the only bully on the block: China, too, uses a full suite of economic, diplomatic and military weapons to enforce fealty within its PWLO alternative, the Belt and Road Initiative, and in its neighborhood.8 Growing Global bifurcation – the cleaving of the world into American and Chinese spheres – implies that countries increasingly face a choose of which master, not if they will be mastered.

Inevitable and irreversible Global bifurcation

Four factors are driving the world to inevitable and irreversible Global bifurcation: (1) Global entropy’s erosion of national and trade security; (2) automated Localization’s erosion of the economics of globalized supply chains; (3) scale and first-mover economics concentrating technological leadership in the US and China; and (4) rising strategic competition to shape the PWLO’s successor order. Given the speed of advancement and immense scale of cutting-edge technologies, few if any countries now can compete with the US or China, especially as each moves to control critical inputs. The necessity of these technologies for economic development and protection from AI-enabled, long-range precision missiles, and space-based weapons they can’t afford, forces countries to choose a famiglia within the emerging Cosa Nostra order.

Hofstede herding

While geography is sure to factor into that choice, the determinative factors likely will be cultural distance of the sort shown in Figure 2, and the degrees of freedom each capo famiglia allows its client states, itself a function of cultural values. Figure 2 may be helpful in sorting where countries align, but not necessarily when.9 For that, Geert Hofstede’s six-factor cultural model of behavior may be helpful in predicting the pace of both trade and security negotiations.10 For instance, even though Japan, South Korea and the EU all disdain bargaining and were offended by President Trump’s approach, each came to a deal quickly due to strong tendencies for “uncertainty avoidance” within their respective cultures. Indonesia and Vietnam instead overcame their offense to strike deals based on perceived inferiority in the global pecking order and deeply seated hierarchical cultures (high “power distance” in Hofstede’s terminology). Conversely, strong individualism and low power distance makes a country like Canada less willing to come to a deal, even though both geography and culture make clear that it will eventually choose America over China.

The high-roller table: ignore at your peril

Cultures are complex and fickle, which is part of why international relations is. Like most of President Trump’s policies, his apparent foreign policy strategy – at least as I, an outsider, perceive it = is high-stakes gambling. When you engage in brinksmanship, which appears to be his preferred style, you must accept that you might lose and that if you do it repeatedly, you eventually will. In cards, mathematical probabilities tell you how often but not when. In international relations where the interaction of complex, fickle cultures are at play, even the odds are hidden by Uncertainty.

It’s easy for market professionals working on trading floors populated by every race and creed in the global financial capitals of London, New York and Singapore to dismiss “culture” as a driver of markets. But in the rising La Cosa Nostra international order, understanding the “cultural geography” is an essential input to investment decisions. Prepare appropriately.

It’s a universal value to show your appreciation with a ❤️ and to share this article!

Financial Disclosure and Disclaimer

The information provided in Seriously, Marvin?! or referred to in Thematic Markets is for informational purposes only and are not intended to constitute financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice. The content is prepared without consideration of individual circumstances, financial objectives, or risk tolerances, and readers should not regard the information as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any specific securities, investments, or financial products.

Readers of Seriously, Marvin?! are solely responsible for their own independent analysis, due diligence, and investment decisions. We strongly advise consulting qualified financial professionals or other advisors before making investment decisions or acting on any information provided in our materials.

The information and opinions provided are based on sources believed to be reliable and accurate at the time of publication. However, neither Seriously, Marvin?! nor Thematic Markets, Ltd makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the information. Markets, financial instruments, and macroeconomic conditions are inherently unpredictable, and past performance is not indicative of future results.

Neither Seriously, Marvin?! nor Thematic Markets, Ltd accept liability for any losses, damages, or consequences arising from the use of its content or reliance on the information contained therein. Readers acknowledge that investment decisions carry inherent risks, including the risk of capital loss.

This disclaimer applies globally and shall be enforceable in jurisdictions where Thematic Markets, Ltd, a company incorporated and based in England and Wales, operates. Readers in all jurisdictions, including but not limited to the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, European Union, Australia, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, are responsible for ensuring compliance with local laws, rules, and regulations.

By accessing or using the information provided by Seriously, Marvin?!, users agree to the terms of this disclaimer.

“How Trump’s ‘Shithole Countries’ Comment Echoes a Century of American Immigration Policy,” Olivia B. Waxman, Time, 12 January 2018.

“The Reformation of Rights: Law, Religion, and Human Rights in Early Modern Calvinism,” John Witte, Journal of Church and State, vol. 51, no. 2, Spring 2009; The Myth of Religious Violence, William T. Cavanaugh, Oxford University Press, 2009; “The Political Authority of Secularism in International Relations,” Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, European Journal of International Relations, vol. 10, no. 2, 2004; and Formations of the Secular, Talal Asad, Stanford University Press, 2003.

“Lavrov says US threatens multilateralism, US rejects remarks as ‘whining’,” Michelle Nichols, Reuters, 16 July 2024; “It’s time for the west and the rest to talk to each other as equals,” Kishore Mahbubani, blog post, 12 December 2023; “Genuine Multilateralism and Diplomacy vs the ‘Rules-Based Order’,” Sergei V. Lavrov, Russia in Global Affairs, vol. 21, no. 3, July/September 2023; and “A Conversation with Lee Kuan Yew,” Fareed Zakaria, Foreign Affairs, March/April 1994.

“Haggling Spoken Here: Gender, Class, and Style in US Garage Sale Bargaining,” Gretchen M. Herrman, The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 38, no. 1, July 2004; and “Negotiating culture: conflict and consensus in U.S. garage-sale bargaining,” Gretchen M. Herrman, Ethnology, vol. 42, no. 3, Summer 2003. For a history of the moral roots of Western preferences for transparent pricing see “How the Quakers became unlikely economic innovators by inventing the price tag,” Bronson Arcuri & Benjamin Naddaff-Hafrey (producers), Aeon (video), 3 April 2018.

“Pausing Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Enforcement to Further American Economic and National Security,” The White House (Press release), 10 February 2025.

“How Trump has turned tariffs into diplomatic shakedowns,” James Politi & Aime Williams, Financial Times, 8 August 2025.

“Debt Distress on the Road to ‘Belt and Road’,” Mark A. Green, Wilson Center, 16 January 2024; “Investigating China’s economic coercion: The reach and role of Chinese corporate entities,” William Piekos, Atlantic Council, 6 November 2023; “The Rise and Fall of the BRI,” Nadia Clark, Council on Foreign Relations, 6 April 2025; and “Does China’s Coercive Economic Statecraft Actually Work?” Matt Ferchen, United States Institute of Peace, 1 March 2023.

Note, distances represented in Figure 2 are from average Western values, not each country’s distance from another. Hence, despite their proximity to each other in Figure 2, China and Bolivia are no closer culturally than they are geographically, they’re just similar distances from the US (both culturally and geographically). For perspective, Figure 7 in Global entropy: Enter the dragons shows how culturally distant various nations are from China (or Russia).

The 6‑Dimensions Model of National Culture, Geert Hofstede, website as of 11 August 2025; and Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Geert Hofstede, Geert Jan Hofstede & Michael Minkov, McGraw‑Hill Professional, 3rd edition, 2010.