Ain’t misapplyin’

Past studies have limited applicability to unprecedented trade policy

President Trump’s return to office has irritated a long-bothersome itch of mine. It is a very deep itch, so I can only scratch the surface here by focusing on a single issue of critical importance to the US economic outlook: the medium-to-longer-term effects of President Trump’s tariff policies.

Cash for your trash

Between the leader-of-the-free-world/world’s-richest-man foemance and Los Angeles looking like a normal day in Berkeley when I was an undergrad, it’s a tough week to attract eyeballs, so I’ve decided to spice it up with a contest. The first person to correctly identify the theme of the section headings of this piece in the comments wins a one-month paid subscription to my research at Thematic Markets.

That ain’t right

One of my greatest peeves is the lazy application of past economic studies’ results to a current question without considering differences in context. This is unfortunately common in economic policy analysis, especially when partisan politics interferes.

Donald Trump’s sharp break with what might be called “accepted” policies and his polarizing politics have led to an explosion in such misapplications. Nowhere is this more the case than the Trump Administration’s reversal of a 75-year trend of falling tariffs.

Lookin’ good but feelin’ bad

Readers of Thematic Markets know that I have already addressed the near-term economic impact of tariffs and shown that, despite markets’ and many economists’ histrionics, their direct effects on economic growth are far smaller than, for instance, income tax hikes, because substitution effects partially offset income effects. Here I’m going to focus on the far more important question of what effects tariffs might have on the long-run growth of capex and productivity.

Jitterbug waltz

I do not dispute the headline implications of trade theory and post-WWII empirical research demonstrating that, in most cases, tariffs diminish competition and thereby lower productivity growth. But I believe the current context may be one of the exceptions.

The present situation is wholly unprecedented: the world’s largest, richest, most technologically advanced economy, that is the largest gross and net source of global demand growth despite an unusually low – and falling – trade share of GDP is putting up large tariff walls. Those walls are not going up in a vacuum but in the presence of (and I would argue, largely due to) the massive global distortion created by extensive manufacturing subsidiesin the world’s second-largest economy and (by far) largest manufacturer. There is a lot to unpack there, so let’s take it step by step and relate it to consensus views of trade theory and evidence.

Find out what they like

Let’s start with the nature of the studies showing that falling tariffs increase long-run economic growth by raising productivity growth (the rate of growth of output per worker). The first thing to note is that nearly all of these studies were estimated during the era of “hyperglobalisation” from 1985 to 2010. During this period poor countries converged to wealthier ones at a rate unprecedented in Economic History. That’s important context both theoretically and empirically.

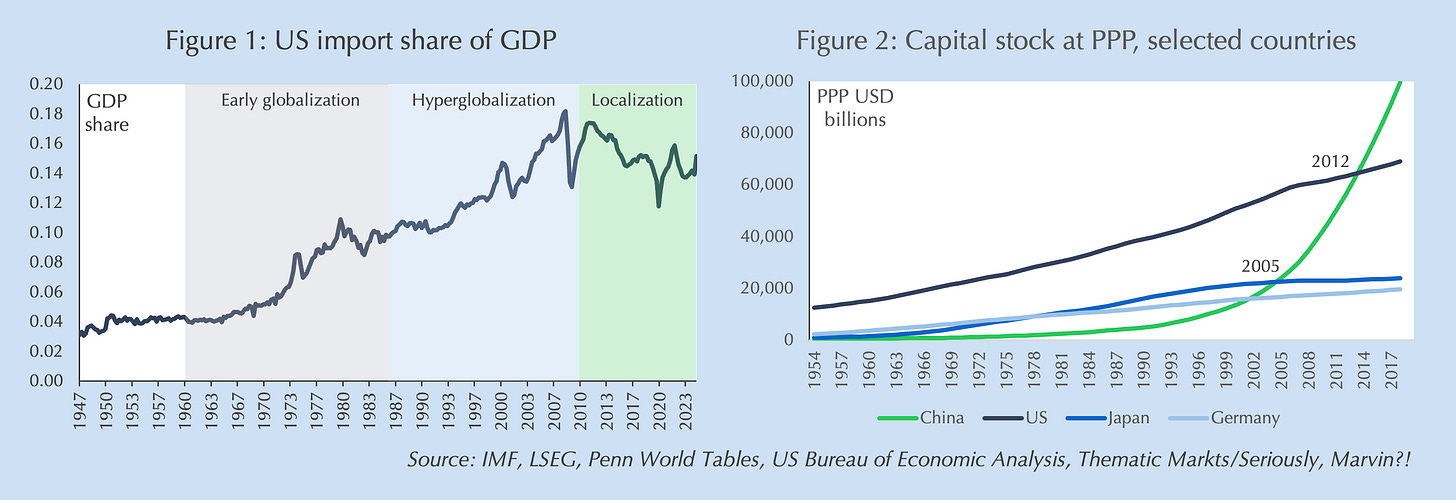

Theoretically, potential gains from trade are greatest between economies at very different stages of development due to the greater potential for specialization of labor. While many developing economies still stand to benefit from trade with the US, it isn’t clear the US continues to enjoy equivalent rewards. A remarkable but largely unnoticed trend of the last two decades is that, even as US growth has outperformed its peers, the US import share of GDP has been falling since 2008 (Figure 1).

Why? Automated Localization. When workers can be replaced by robots or AI, it no longer matters how cheap the labor is in...pick a country...the robot is cheaper and closer to US customers. This turns trade theory – which is all about specialization of labor – on its head. It is no longer clear that trade in anything other than commodities will improve economic efficiency.

Now consider the empirical evidence for productivity gains resulting from lower tariffs. Being almost entirely from the hyperglobalisation era, it isn’t clear that it applies in an age of Localization (which I date from about 2010-’12, Figure 1). More importantly, most of the studies focus on developing economies in the process of convergence – notably Brazil, Chile, India, and Indonesia1 – or from the integration of poorer Eastern Bloc countries with the richer economies of Western Europe through the EU.2 There are several reasons these studies likely do not apply to the United States.

One of the largest sources of productivity growth in the economies studied was the foreign direct investment (FDI) that accompanied a reduction in tariffs.FDI raised capital-to-labor ratios in these poorer countries, directly raising labor productivity.But more importantly, FDI by multinationals brought advanced technologies and manufacturing techniques to these countries, increasing so-called total factor productivity (TFP), i.e. the “know how” to extract even more output from the same capital and labor inputs.3 Since the US already has among the highest capital-to-labor ratios and levels of technological sophistication, it is unlikely to benefit in the same way.

Yacht club swing

The US also is the largest and arguably most competitive marketplace in the world. A confounding but telling feature of many of the post-War studies on the relationship between tariffs and productivity growth is that tariff reductions were part of broader economic liberalization that included deregulation, labor-market reforms, and enhanced competition enforcement. That makes it difficult to distinguish between the effects of tariff reductions and other policy changes.4 But there is no ambiguity over the role of competition in raising productivity: research shows that across countries, new firm entrants are the primary driver of innovation and productivity growth.5 The US economy not only represents a quarter of global GDP by itself, but has among the highest rates of business churn (firm births and deaths) of any economy.6 Tariffs are unlikely to change that.

It is also important to note that not all economic research shows a negative relationship between tariffs and productivity growth. Studies of high-productivity countries, especially ones like the US that do not rely extensively on imported inputs to domestic production, find that tariffs may not harm productivity growth.7 Research into pre-World War II trade also fails to find a negative relationship between tariffs and productivity growth. During the Pax Britannica period of globalization from 1870 to 1910, countries like Germany, Sweden and the United States converged with Great Britain, the sole industrial power of the early 19th century, through rapid productivity growth despite imposing high tariff walls.8

Your feet’s too big

Yet the biggest difference between the current situation and either Economic theory or the conditions underlying past empirical research is the massive distortion field commonly known as China. Most tariff opponents claim that they will result in a misallocation of capital and labor: The US will do too much of what it is less efficient at (manufacturing) and too little of the things in which it has a comparative advantage at (finance and designing iPhones). But this view is based on the wholly false assumption that US capital and labor are optimally allocated now. Nothing could be further from the truth!

Chinese industrial policy has resulted in what is likely the greatest misallocation of resources in human history. Figure 2 displays a 70-year history of the real value of China’s capital stock and those of the three largest industrialized economies. The exponential growth of China’s capital stock makes Japan’s investment bubble from the 1980s – the one that led to Japan’s lost decade – look like a molehill.

While many economists assume that China’s rapid industrialization reflects its cheap labor and comparative advantages, the facts tell a very different story. The exponential growth of China’s capital stock into a behemoth that wields 40% of global manufacturing capacity has little to do with wage rates and everything to do with industrial policy on a scale never seen before. In an analysis that likely undercounts indirect loan subsidies, the CSIS estimates that China spends 1.7 percentage points of GDP per year on industrial policy, more than double the next highest of any other major economy.9 As Michael Pettis puts it, “Not only does it have the highest investment share of GDP in history, but even if China were to reduce that share by 10 percentage points, it would still be one of the highest investing countries in the world.”10

Black and blue

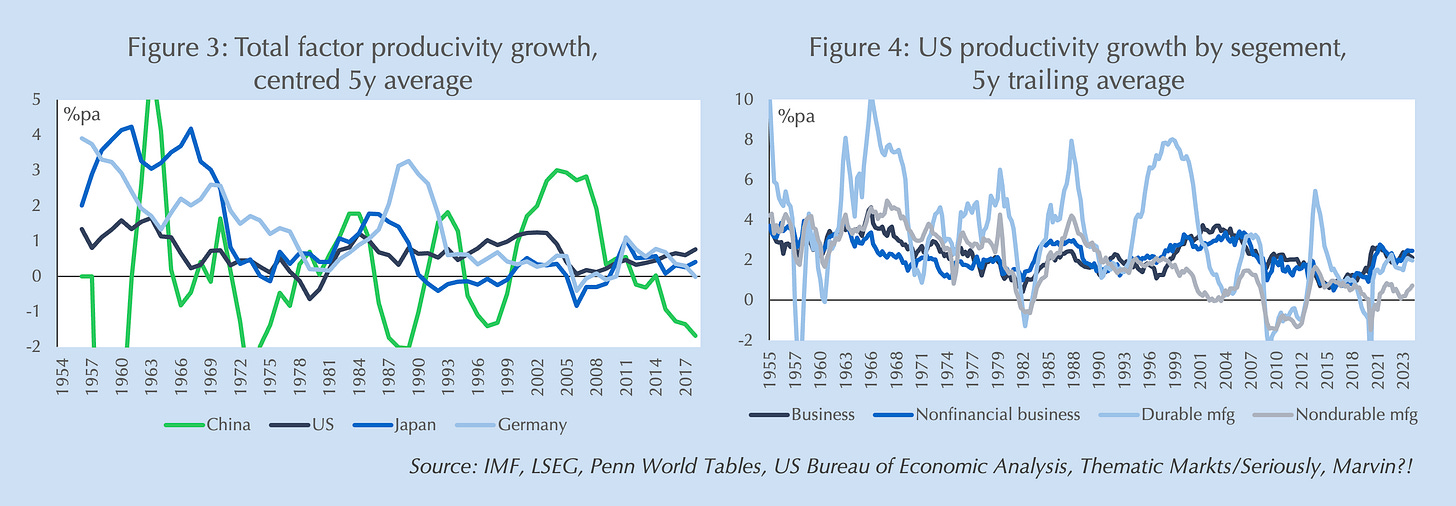

Figure 3 shows the effect of this misallocation of capital: more than a decade of negative total factor productivity growth. That is, since 2011, every dollar of investment in China has yielded less than a dollar in value-added output and would have been better invested in Germany, Japan or the United States. It’s not just electric vehicles. China’s misallocation of savings to inefficient domestic investment has flooded the world with loss-accruing products across categories. That in turn has undermined otherwise competitive, productive manufacturers in the West, forcing them into run-off or into bankruptcy. In Incompatible drag (a free article at Thematic Markets), I presented evidence tying the collapse in manufacturing productivity across advanced economies since 2008 directly to Chinese import penetration.

Thus, we can definitively say that the current mix of capital and labor in the United States (and other economies) bears no resemblance to “optimality.” Whether and how tariffs might restore optimal allocations are the questions economists should be asking, not simply if tariffs are “good” or “bad” for growth.

Notably, US manufacturing productivity, though still low, has trended higher for roughly the last eight years (Figure 4). While the trend began before the first imposition of US tariffs on China in 2018, suggesting that something else (Localization) is behind it, the rate of productivity growth has steadily climbed despite the tariffs, flying in the face of the consensus view that tariffs would retard productivity growth.

I’ve got my fingers crossed

My rather non-consensus view is that a broad, sizeable tariff moat – one that helps preclude redirection of Chinese exports through third countries – likely will boost the rate of US productivity growth. Yes, it will lead to a reallocation of capital and labor from some higher margin industries – indeed, that’s the point – temporarily reducing the level of output per worker. But it should reinvigorate growth of new firms and innovation in manufacturing, the sector that has historically been responsible for most US productivity growth.

The joint is jumpin’

As a supporting anecdote, last week I spoke with the CEO of a US specialty materials manufacturer. He is thrilled about the tariffs. He told me that under “free trade” there is no way manufacturers like him could compete with Chinese subsidies. Because of the US tariff policy, he expects to increase production by 50% next year and 100% the year after, i.e. a three-times increase in production over two years.

Incoming investment numbers suggest he’s not alone.US firms’ capex spending in the first quarter was extraordinarily strong and the growth of spending on equipment was the highest on record.Further, as I compiled inObservations: 100 days of turmoil, known unknowns, through the end of April, year-to-date announced new US capex totaled $2 trillion.The comparable number for the European Union?Just $7 billion.Note that’s trillions versus billions.Not that I do, but even if you want to assume that 90% of announced US investments were politically driven – appeasing the man in the White House – that’s still almost 30 times announced investment in Europe, a similar-sized economy.So much for tariffUncertainty, or at least its expected ill effects on US investment.

Two sleepy people

Not all companies are going to benefit from tariffs. There will be creative destruction in the reallocation of workers and capital. But I suspect the net contributions to growth from firms that expand will outweigh the net subtractions from tariffs’ losers. Thus, US growth is likely to be volatile, but a recession is unlikely and I expect growth will average better than 2% over the next year. The rest of the world? That will depend on whether they join the US behind the moat, or continue to suffer from Chinese excess capacity.

Don’t forget to comment, and there’s no such thing as a misapplied ❤️!

Financial Disclosure and Disclaimer

The information provided in Seriously, Marvin?! or referred to in Thematic Markets is for informational purposes only and are not intended to constitute financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice. The content is prepared without consideration of individual circumstances, financial objectives, or risk tolerances, and readers should not regard the information as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any specific securities, investments, or financial products.

Readers of Seriously, Marvin?! are solely responsible for their own independent analysis, due diligence, and investment decisions. We strongly advise consulting qualified financial professionals or other advisors before making investment decisions or acting on any information provided in our materials.

The information and opinions provided are based on sources believed to be reliable and accurate at the time of publication. However, neither Seriously, Marvin?! nor Thematic Markets, Ltd makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the information. Markets, financial instruments, and macroeconomic conditions are inherently unpredictable, and past performance is not indicative of future results.

Neither Seriously, Marvin?! nor Thematic Markets, Ltd accept liability for any losses, damages, or consequences arising from the use of its content or reliance on the information contained therein. Readers acknowledge that investment decisions carry inherent risks, including the risk of capital loss.

This disclaimer applies globally and shall be enforceable in jurisdictions where Thematic Markets, Ltd, a company incorporated and based in England and Wales, operates. Readers in all jurisdictions, including but not limited to the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, European Union, Australia, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, are responsible for ensuring compliance with local laws, rules, and regulations.

By accessing or using the information provided by Seriously, Marvin?!, users agree to the terms of this disclaimer.

“Trade Liberalization and Firm Productivity: The Case of India,” Petia Topalova & Amit Khandelwal, The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 93, no. 3, pp. 995–1009, 1 August 2011; “Barriers to Competition and Productivity: Evidence from India,” Sivadasan Jagadeesh, The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1-66, September2009; “Trade Liberalization, Intermediate Inputs, and Productivity: Evidence from Indonesia,” Mary Amiti & Jozef Konings, American Economic Review, vol. 97, no. 5, pp. 1611–1638, December 2007; “Heterogeneous productivity response to tariff reduction. Evidence from Brazilian manufacturing firms,” Adriana Schor, Journal of Development Economics, vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 373-396, December 2004; “Trade, Technology, and Productivity: A Study of Brazilian Manufacturers, 1986-1998,” Marc-Andreas Muendler, CESifo Working Paper Series 1148, 2004; and “Trade Liberalization, Exit, and Productivity Improvements: Evidence from Chilean Plants,” Nina Pavcnik, The Review of Economic Studies, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 245–276, January 2002.

“Unit Labor Costs in the Eurozone: The Competitiveness Debate Again,” Jesus Felipe & Utsav Kumar, Review of Keynesian Economics, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 490-507, October. 2010.

“Does Foreign Direct Investment Increase the Productivity of Domestic Firms? In Search of Spillovers Through Backward Linkages,” Beata Smarzynska Javorcik, American Economic Review, vol. 94, no. 3, pp 605-627, June 2004; “Multinational Corporations and Spillovers,” Magnus Blomström & Ari Kokko, Journal of Economic Surveys, vol. 12, no. 13, pp. 247-277, 16 December 2002; “Multinational enterprises, technology diffusion, and host country productivity growth,” Bin Xu, Journal of Development Economics, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 477-493, August 2000; “How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth?” Eduardo Borensztein, Jose De Gregorio, & Jong-Wha Lee, Journal of International Economics, vol. 45, pp. 115-135, 1998.

“The Limits of Trade Policy Reform in Developing Countries,” Dani Rodrik, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 6, no.1, pp. 87-105, Winter 1992; and “Productivity, imperfect competition and trade reform: Theory and evidence,” Ann E. Harrison, Journal of International Economics, vol. 36, no. 1-2, pp. 53-73, February 1994.

“Firm Entry and Exit and Aggregate Growth,” Jose Asturias, Sewon Hur, Timothy J. Kehoe, & Kim J. Ruhl, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, vol. 15, no.1, pp. 48–105, January 2023; “Entry, Exit and Productivity: Empirical Results for German Manufacturing Industries,” Joachim Wagner, German Economic Review, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 78-85, 6 January 2010; “The Effects of Entry on Incumbent Innovation and Productivity,” Philippe Aghion, Richard Blundell, Rachel Griffith, Peter Howitt, & Susanne Prantl, The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 91, no. 1, pp. 20–32, February 2009; “The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity,” Marc J. Melitz, Econometrica, vol. 71, no. 6, pp. 1695-1725, November 2003; and “Trade Liberalization, Exit, and Productivity Improvements: Evidence from Chilean Plants,” Nina Pavcnik, The Review of Economic Studies, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 245–276, January 2002.

“Business Policies and New Firm Birth Rates Internationally,” John R. Nofsinger & Reca Blerina, Accounting and Finance Research, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 5477-5477 September 2014.

“The effects of input tariffs on productivity: panel data evidence for OECD countries,” Maria Bas, Åsa Johansson, Fabrice Murtin, & Giuseppe Nicoletti, Review of World Economics, vol. 152, pp. 401–424, 2016.

“Protectionism and Economic Growth: Causal Evidence from the First Era of Globalization,” Niklas Potrafke, Fabian Ruthardt, & Kaspar Wüthrich, CESifo working paper, 2020; and “Trade and Economic Growth: Historical Evidence,” Moritz Schularick & Solomos Solomou, Cambridge University working paper, September 2009.

“Red Ink: Estimating Chinese Industrial Policy Spending in Comparative Perspective,” Gerard DiPippo, Ilaria Mazzocco, Scott Kennedy, & Matthew P. Goodman, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 23 May 2022.

“Open Questions: Economist Michael Pettis on China’s consumption paradox and the pitfalls of a trade war,” Carol Yang (interview), South China Morning Post, 24 March 2025.

Productivity & profits, the two things missing from the China miracle!! Hmmmmm, if only there were something like a . . . like an invisible hand that helped allocate capital in an intelligent way!?!

Thank you for clarifying a few key underlying assumptions of the past 50+ years of economic research. I have been spending a lot of time musing on a quote recently and your insights clarify why it feels so prescient:

"The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones."

-John Maynard Keynes